Known as “Mr Copper”, “Hammer”, or most famously “Mr Five Percent”, Yasuo Hamanaka was one of the most feared and respected copper traders. His nicknames indicative of the power he was thought to wield over the global copper market.

During the early 1990’s his employer, the Japanese trading company Sumitomo Corporation adorned its head copper trader with a double page spread in its glossy annual report. Hamanaka was quoted as saying that their control over the copper market was due to his “expertise in risk management”.

Sumitomo began as a supplier of copper to Japan’s shoguns in the early 17th Century. By the late 20th Century it had evolved into a large diversified trader of metals, grains and a wide variety of industrial and consumer products. But despite its size it was still dwarfed by its rivals – Mitsubishi and Mitsui – and unlike its rivals it had no copper mines of its own, and so no access to the physical raw material.

Prior to 1986 Hamanaka purchased and sold physical copper as a trader for the Non-Ferrous Metals Department of Sumitomo. At some point in 1986 Hamanaka was promoted to the position of head copper trader. His elevation up the ranks was not a happy one. In the three year period after Hamanaka’s appointment the Sumitomo copper team suffered tremendous losses, apparently unbeknownst to upper management. The dramatic losses the resulted of a combination of physical and futures copper trading by Hamanaka, which in turn were an apparent attempt to recover from an even earlier physical copper trade that had gone sour.

According to a subsequent investigation by the CFTC, Hamanaka “lied to his superiors, destroyed documents, falsified trading data and forged signatures” in order to hide his losses. Hamanaka hid the records of his unauthorised trading in a book – a secret account of what was by then a familiar way for dodgy traders to keep track of their unauthorised trading.

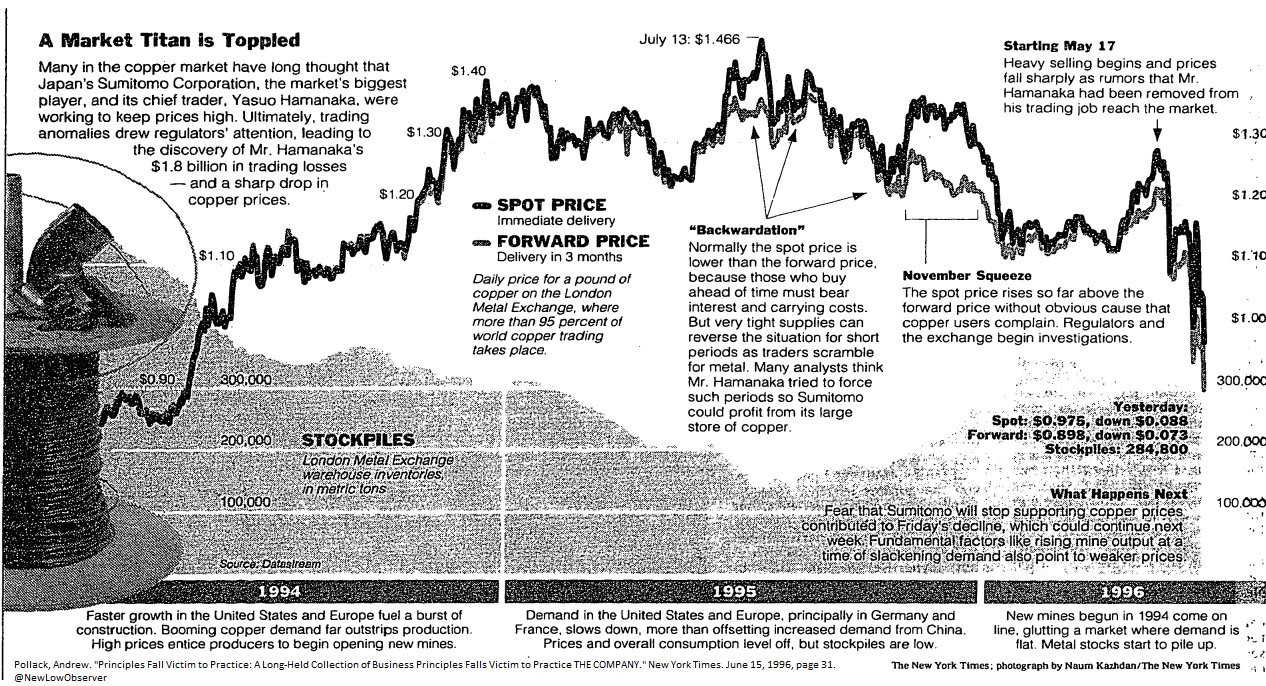

Not one to give up easily or to come clean to his bosses, Hamanaka attempted to redeem himself. And so in the early 1990’s he set out to devise a plan that would allow him to control the price of copper, and recover from his previous losses…before his bosses ever found out. As the copper price rose during 1994 on the back of a resurgence in copper demand after the early 1990’s recession all the ingredients were in place to manipulate the market higher.

First, Hamanaka entered into a string of intricate agreements with private metal trading firm Global, whereby Sumitomo agreed to make monthly purchases of copper between 1994 and 1997. The agreements took the form of a series of supply contracts that contained unusual minimum price and price participation provisions. The goal of these agreements was to establish the appearance of genuine commercial need to obtain physical copper.

Global would purchase copper warrants’ from a Zambian copper producer. It would then sell the copper to Sumitomo, and finally Sumitomo would complete the circle by selling the same amount of copper back to the Zambian firm. This gave Hamanaka the justification (in the eyes of the regulators) to establish a large futures position in order to hedge the illusory delivery of the physical copper.

Second, Hamananka opened an account with Merril Lynch known as the “B” account which was authorised to trade using Sumitomo’s vast credit line. By autumn 1995 Global had bought 780 thousand tonnes of copper futures, another 1.2 million tonnes were acquired by Hamananka through other brokerages along with half of LME copper warrants.

He then began to unwind some of the futures positions by taking physical delivery of the copper when the futures positions expired. This meant he could then carry out the next part of the plan – control of the copper cash market. By November 1995 he controlled almost 100% of the LME warehouse receipts, enabling him to dictate prices to traders who had shorted copper futures; either they had to deliver physical copper or close out their positions at a premium.

The extremely tight physical market resulted in a huge backwardation (i.e. the spot price exceeded the futures price) to appear in the market. After numerous complaints from both futures market participants and physical buyers an investigation eventually uncovered the unauthorised trading. He was removed from his post on 9th May 1996, but it was 10 days later that rumours of the scheme and Hamananka’s removal reached the market. Once that happened the price of copper crashed as traders realised that the artificial support would have to be unwound.

After initially admitting it had lost $1.8 billion on the manipulation, losses eventually swelled to around $2.6 billion as the positions were unwound into a market scarred by the announcement and an increase in copper production around the globe.

Although market reforms mean that the type of long-term manipulation of copper carried out by Hamananka should be impossible today, that doesn’t mean it can’t happen over a short-term basis, especially if a speculative fervor in the market develops.

Related article: No silver lining: Why the Hunt brothers bet on silver was doomed to fail