Stagflation is a situation where inflation soars, economic growth slows and unemployment spikes. It presents the worst of all dilemmas to policymakers. Efforts to control inflation tend to make unemployment worse, while targeting unemployment tends to result in higher inflation.

The 1970’s marked the last period of stagflation. An expansive monetary policy during the 1970’s combined with a supply shock (a surge in oil prices) resulted in high inflation. Cost push inflation combined with increased competition decimated many energy intensive industries. Collective wage bargaining and unionised labour resulted in strikes and other restrictions on the supply of labour as people attempted to recover their lost purchasing power. The result was a deep recession.

Fast forward to 2020.

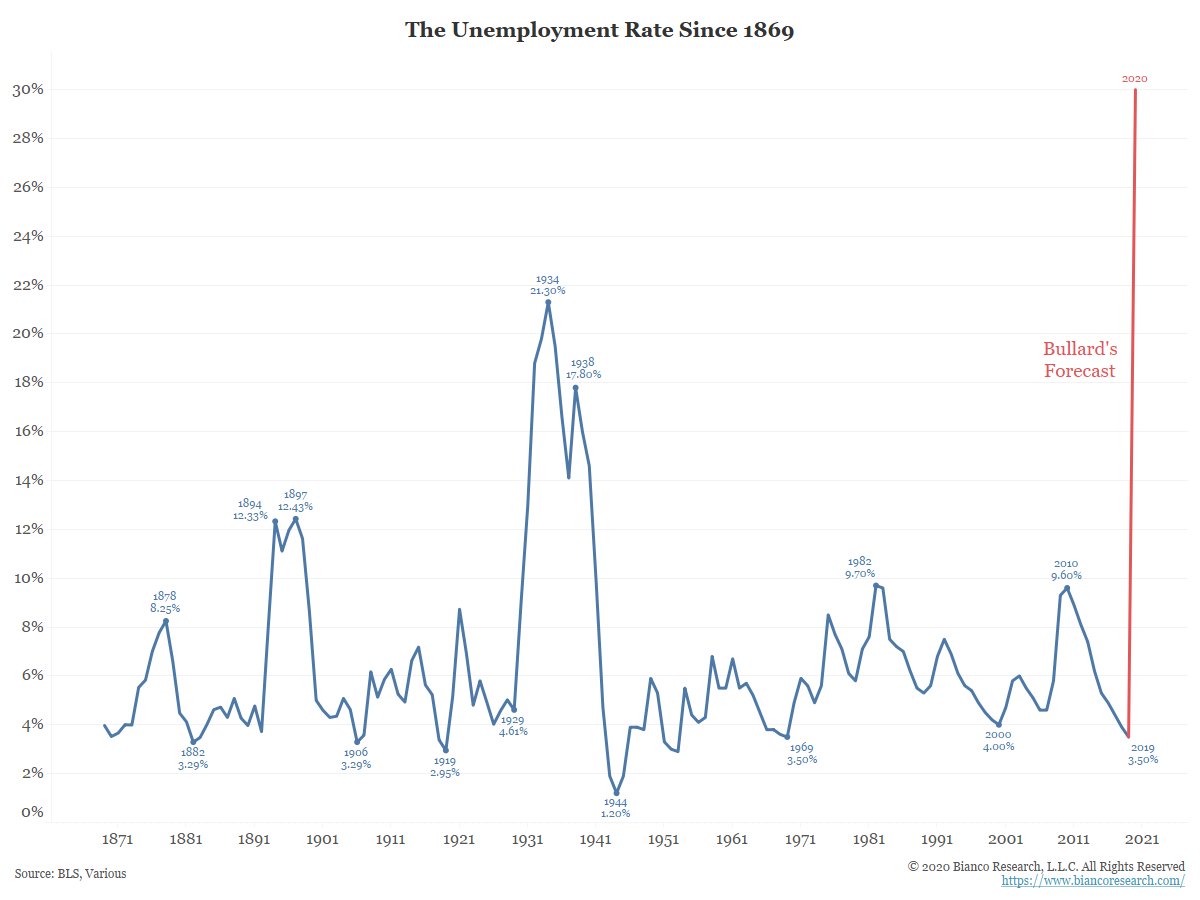

The global pandemic has evidently resulted in a demand shock. Consumers face lock-down in many countries. Unable or unwilling to frequent areas with large numbers of people, travel has dropped like a stone while discretionary spending on eating out and other services has been decimated. Manufacturing activity related to travel (cars, planes etc.) face a particularly perilous future. Unemployment is set to soar as companies face the prospect of months of demand destruction, uncertain of when or even if demand will ever return (chart below shows the forecast for US unemployment).

Meanwhile consumers face shortages of basic essentials in the shops. What began as panic buying of toilet rolls, pasta, bread and tinned food is morphing into a supply shock as logistical operations are put under immense strain. Border closures, staff sickness and lack of spare capacity mean that essential products are not in the right place at the right time.

Luckily, global stocks of agricultural commodities are healthy. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) global wheat stocks at the end of the crop marketing year in June are projected to rise to 287.14 million tonnes, up from 277.57 million tonnes a year ago. Meanwhile, rice stocks are projected at 182.3 million tonnes versus 175.3 million tonnes a year ago.

But it doesn’t matter if there is enough for everyone if no one can get hold of it. Countries concerned about supplies available to their citizens may make the situation worse.

“All you need is panic buying from big importers such as millers or governments to create a crisis,” said Abdolreza Abbassian, chief economist at the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

“It is not a supply issue, but it is a behavioural change over food security,” he explained in an interview with Reuters. “What if bulk buyers think they can’t get wheat or rice shipments in May or June? That is what could lead to a global food supply crisis.”

Other commodities face similar supply-side constraints. Mining operations – typically operating in remote regions – are cutting operations to protect their staff from a virus outbreak. Even those mines which are not labour intensive face the same logistical issues as agriculture. A lack of labour to drive trucks and delays or closure of port facilities.

The trick to navigating crises is not necessarily the crisis itself but how policymakers respond: the mistakes they inevitably make and the second order consequences of their actions. With that in mind consider the barrage of monetary and fiscal stimulus that countries are injecting into the economic patient.

Last week The International Monetary Fund called for a “coordinated and synchronised global fiscal stimulus” to bolster the world economy. While the economic ‘flywheel’ has come to an abrupt stop, giving people more money and cutting interest rates will not be enough to get things going again.

The evidence from China suggests that it is only through state directed activity will economic growth get back to any semblance of normality. In the absence of private sector demand governments everywhere are going to have to introduce massive infrastructure spending to restart the economic ‘flywheel’ and unplug the logistical bottlenecks that have infected supply chains.

Prominent Chinese economist and former central bank adviser Yu Yongding argues that while China has more fiscal and monetary policy room to manoeuvre than its counterparts in Europe and the United States, the country’s top priority should be to focus on epidemic control and the full resumption of production in factories closed during the height of the outbreak.

The lesson from the 1970’s is that it is only through supply side measures will you be able to bolster the economy while avoiding rampant inflation. The viral pandemic which has swamped the globe and may involve more than one wave of infection. In much the same way shortages will burst open and spread across the globe. In turn this will drive prices higher as people and countries fear not being able to secure the products and resources they need. Injecting the economy with trillions of more dollars is like throwing kerosene on the fire.